Who you gonna call?

A criminology primer for the deadly serious

Police contact psychic in Ray Gricar disappearance

Psychic contacts writer Bill Keisling

Keisling consults oracles,

contacts one of Jonathan Luna's closest friends,

who offers keen insights into Luna's 'victimology'by Bill Keisling

Posted May 10, 2005 -- In a strange twist to an already strange case, a psychic tells me she's been "officially" contacted by Bellefonte, Pa, police to help locate missing Centre County District Attorney Ray Gricar. This news comes only a few weeks after authorities amazingly said they were disinclined to look into actual cases prosecuted by Gricar to help explain his disappearance.

A psychic by nature deals with the world of scary, if imaginary, happenings. The irony is, the real-world explanation to Gricar's disappearance may be scarier than many executives in the corporate media and law enforcement may want to ponder.

The psychic, Carla Baron, says she's also under contract with Court TV, which likes to call itself "The Investigation Channel." Baron's involvement comes at a time when the corporate news and entertainment media, like the authorities, continue to refuse to look into the hard facts, and the record of growing public corruption, surrounding the vanishings of both Gricar and slain federal prosecutor Jonathan Luna.

It gets stranger. Who's a psychic gonna call when she needs insight to such a perplexing series of events as the vanishing of prosecutors? Who else, but the guy who's done the research -- your writer, me.

I first received communications from psychic Baron a few nights ago, not be seance, or portal projection, but by e-mail. I received the e-mail out of the great blue from Baron about 3:30am the other morning. The e-mail complemented me on my article previously posted here, "Fear and Loathing, Denial and Deceit, in Happy Valley."

"I just want to express that I was impressed with your latest piece on the missing DA, Ray Gricar," Baron wrote me. "You do have a gift."

My spider senses were tingling. (Those readers who may have followed my writings perhaps know that I began my national scribbling career covering the meltdown at the atomic generating station at Three Mile Island in 1979. I stood across the Susquehanna River looking at that nuclear plant for days at the height of the crisis, so I have radioactive blood, and a healthy distrust of some things.)

I replied to the e-mail from Ms. Baron by thanking my mystery correspondent for her kind words. What was she doing up so late? I asked. Was she a student?

Who you gonna call? Carla Baron (right) communicates from beyond the void to say, 'I have been officially requested to work on the Gricar disappearance this past week by the family/police'

"Not a student. Used to be some years ago," came her cryptic reply. "If you click on my site, you can read some on the work I do." I clicked the link, and read about Baron's involvement with a previous murder investigation in State College, and her growing list of media outlets where she talks about her prognostications.

Supposed psychics in cases like Gricar's can sometimes be useful, but not in the way the media has led the public to believe. Psychics really don't have the answers. The answers, bet your bottom dollar, are instead found in very real places, like the court records of the cases prosecuted by Gricar and Luna. As we see in the Gricar investigation, an investigator's mind often is his or her biggest obstacle. So a psychic can sometimes be a valid brainstorming tool, to help you to look at a case in a way you may not have previously considered, or to help toss out fresh ideas.

But, as Sherlock Holmes would say, bet on deductive reasoning every time, not communications from the spirit world. A psychic at most is a condiment, not the meat. A side show, not the main event.

Even so, as we all know, talking to a psychic can most always be fun. So I asked Baron to give me her sense of whether she felt Jonathan Luna and Ray Gricar had met their strange fates in the company of a stranger, or with someone they knew. In a way, it was a loaded question. It assumes someone was with them. In both cases, as I'll discuss, it's the invisible heart of the mystery.

My question prompted my correspondent to finally lay her tarot cards on the table.

"Actually," she replied this past Saturday morning, May 7, 2005, "I'm one step ahead here. I have been officially requested to work on the Gricar disappearance this past week by the family/ police, and been in a couple of sessions already with Det. Zaccagni and the designated family contact (don't wish to reveal which one until this is made public - should be this week.) In fact - I have another reading @ 11 am with this woman to try and 'hone in' further, and a call to return to the detective following that. "So .. it is my policy to only discuss the details of those reads with immediate family, law enforcement, and selected media. That way, confusion will not ensue due to various 'interpretations' of the material presented. It keeps things contained and more precise. This is essential where so much is at stake in these situations for all concerned."

Whether Baron was a step ahead, or a step behind, I leave others to decide. Suffice to say, alarm bells sounded in my head like sirens around a leaky nuke. There were several problems here, aside from Baron's obscuration of her "official" contacts to the Gricar missing person case, which I wondered why she hadn't told me about in the first place.

First, there's the issue of hokum. Baron writes she doesn't want to "discuss the details" so that "confusion will not ensue due to the various 'interpretations' of the material presented," and so on. What was she talking about? Did she fear ghosts would be tipped off that her "investigation" was under way?

'What was she talking about? Did she fear ghosts would be tipped off that her 'investigation' was under way?'

What I divine her to means is, she, and the "selected media," would rather like to control the spin in this public case. Spin control is a problem when you're working with the vaporous divinations of a psychic. No use having the public talking about Jesse James having shot himself in the back, when the ripples in the pool of water also suggest Robert Ford may have pulled the trigger.

Spin control, on the other hand, is not necessary when you have before you hard investigative facts. Like the complete facts of the heroin cases which Gricar and Luna were both prosecuting at the time of their mysterious disappearances.

I also felt strange vibrations about Baron's reference to "selected media." A writer friend of mine, who happens to be a Columbia Journalism School grad, suggested, shall we say, that I was perhaps being offered an opportunity to join the ranks of the "selected media" somehow associated with Baron. We decided it would be best for all concerned to discover where, or how, or whether money fit into all this.

"Are you ever paid by the police and family, as in the Gricar case? If not, are you able to collect a fee from the media to offset your expenses?" I asked Baron.

Baron replied, "I receive no monetary compensation for cases I decide to take on officially, Bill. The media does not pay me, either. I do have a contract as official psychic spokesperson for Court TV, but not in any way associated with these cases. "I also am under contract to soon begin filming a new series for Court TV entitled 'Haunting Evidence.'

"I do other select paid private sessions, and am fortunate to have more than enough work come my way. In fact, sometimes I cannot read all those that would like a session. So, the investigations are my way of utilizing my skills in a productive way, and giving back to 'balance the karmic scales.'"

Finding the truth: 'A successful profiler is not a psychic'

Fair enough, I suppose. But, ultimately, at least here on earth, we're talking about the scales of justice, not of karma. And we can't afford to waste time. So let's get to the heart of the matter, in this, the real world.

"The ultimate aim of an investigation is to solve the mystery, and the questions, and reveal the truth," writes Michael R. King in an essay, "A Multidisciplinary Approach to Solving Cold Cases." The essay appears in a book titled, Profilers: Leading Investigators Take You Inside the Criminal Mind (edited by John H. Campbell and Don DeNevi, Prometheus Books, 2004).

'Revelation of the truth is the primary and critical foundation to final resolution. For without the truth, and indisputable facts, a conclusion will never be reached to precisely solve the mystery.'

"Revelation of the truth is the primary and critical foundation to final resolution," King writes. "For without the truth, and indisputable facts, a conclusion will never be reached to precisely solve the mystery."

Using a psychic in a criminal investigation, as I say, can sometimes prove helpful for police. Especially when they're stumped. It also serves to send a signal they've reached a level of exasperation. Problem is, sooner or later, investigators must make a concrete case, out of real evidence. And that's certainly a problem in the Gricar case. That's why serious, science-minded criminologists have come to rely on what's called a "profile," or a criminal investigative analysis, and not a psychic.

"Violent crimes can be profiled only if residual offender pychopathology can be identified," writes FBI Special Agent Mary Ellen O'Toole, in her excellent essay, "Criminal Profiling: The FBI Uses Criminal Investigative Analysis to Solve Crimes," also contained in Profilers.

"A profile, or criminal investigative analysis, is an investigative tool, and its value is measured in terms of how much assistance it provides to an investigator," O'Toole writes. "Police reports, crime scene photographs, witness statements, forensic laboratory reports, and, if the cases is a homicide, autopsy photographs are provided by the investigating law enforcement agency and are thoroughly examined for the smallest behavioral detail or nuance. Through this intense review process, a 'behavioral blueprint' of the crime and the offender can be constructed. This blueprint allows a profiler to re-create what happened at the scene." (Emphasis mine.)

O'Toole continues, "What qualities or traits constitute a good profiler? Contrary to the current television and movie depictions in which a profiler can 'just see it happening,' a successful profiler is not a psychic. An experienced and well-trained profiler is intuitive, has a great deal of common sense, and is able to think and evaluate information in a concise and logical manner. A successful profiler also is able to suppress his or her personal feelings about the crime by viewing the scene and the offender-victim interaction from an analytical point of view. Most important, a successful profiler is able to view the crime from the offender's perspective rather than his or her own."

"It was not until the mid 1970s that profiling started to become a more refined process," O'Toole recounts. "Research conducted by the FBI into serial murderers and rapists provided a much greater understanding of these offenders and the often complex, curious, and unique behavior they display at their crime scenes."

What are some of these behaviors? O'Toole explains, "Several behavioral characteristics that can be identified at the scene include the 1) amount of planning that went into the crime, 2) degree of control used by the offender, 3) escalation of emotion at the scene, 4) risk level of both the offender and victim, and 5) appearance of the crime scene (disorganized versus organized.)"

A profile of the offender is only half the story. To reconstruct a vanishing, such as those visited upon Luna and Gricar, we must know the victim. This is called, the book Profilers tell us, victimology.

"The key to crime analysis is victimology -- the study of the victim," writes King. "By examining who the victim is, we begin to unravel and eliminate an often perplexing web of misguided leads. A thorough understanding of the victim can often lead the investigation toward a probable suspect rather than to a reaction to an endless pool of less likely possible candidates. According to the Crime Classification Manual, written by the FBI:

Victimology is often the most beneficial investigative tool in classifying and solving a violent crime. It is a crucial part of crime analysis. Through it the investigator tries to evaluate why this particular person was targeted for a violent crime. Very often, just answering the question will lead the investigator to the motive, which will lead to the offender. Victimology is an essential step in arriving at a possible motive. If investigators fail to obtain complete victim histories, they may be overlooking information that could quickly direct their investigations to motives and to suspects."

Who then, we must ask ourselves, were Jonathan Luna and Ray Gricar? How did they occupy their lives? The short answer is that they were prosecutors, prosecuting violent criminals. This is hardly a small and nuanced detail. It may well be the most important detail. We must consider the strong probability that these things happened to these men because they are prosecutors. If we don't want to consider that, hang it up, and let's go watch Ghost Week on the Discovery Channel.

Recontructing Jonathan

As a writer, and a novelist, I'm interested in the psychological motivations of characters in a story. Writers have long blazed ground in this area. Dostoyevsky published his amazing psychological novel Crime and Punishment in 1866, years before Freud and the FBI crime lab. "Life is in ourselves and not in the external," he wrote. And let's not forget The Bard.

Luna victimology Piecing together the puzzle of who was Jonathan Luna?

In the case of Jonathan Luna, before I began writing about him, I felt I must try to place myself in his shoes. What was important to Luna? Aside from his family and friends, Justice. He'd want to see justice done. In my mind I began to try to reconstruct Jonathan. If I was Jonathan, I reasoned, and I was brutally tortured and murdered, I certainly wouldn't want people to think I'd done this horrible thing to myself. I'd want justice for my murder. So I've come to take great offense at lazy, or self-serving, suicide theories.

The deep irony is that some authorities, and the mass media, have turned away from investigating the hard facts of Luna and Gricar's professional roles, and the records of their cases. It's sad for the memory of both men, who may well have died in their pursuit of justice, and the truth.

And now someone has brought in a psychic. Why not give the uniformed public the happy notion that something is being done to solve the crime when, in fact, authorities have said, little of substance is being done.

That a psychic would be asked to get in touch with the spirits in the Ray Gricar vanishing in some sense eerily hits close to the mark. Don't let the smoke screen of the supposed sightings, or other long recitations of the bare facts of either case confuse you. In both Luna and Gricar cases, strangest of all, at the very heart of the riddle, lies the remarkable debate: whether either man encountered anyone at all at the time of his disappearance. That's right, it's almost as if the culprit is a spirit, so apparently devoid are both crime scenes of certain, usable clues. But the culprit's not a spirit.

So clean is the scene. But that's a clue. It means, in my estimation, someone knew that both Luna and Gricar worked in law enforcement, and expected full well that every cop and crime lab on the east coast would be on the case. So the culprit also had to know how to foil the cops and the crime labs, and not leave clues. Ask yourself, who has the knowledge and wherewithal to do that?

'You don't think he was alone either, do you?'

One of the most riveting experiences of my life came when I recently met former Lancaster County Coroner Dr. Barry Walp. I visited Walp to give him a copy of my book on Jonathan Luna. Walp, I'll never forget, looked at me as if from the bottom of a well, and asked, "So you don't think he was alone either, do you?"

The Lancaster coroner's office, in the year following Luna's death, came under highly curious pressure from the FBI to recant the official homicide finding and change the ruling of Luna's death to that of suicide. The coroner's office resisted the pressure, and the death stands as a homicide.

I shook my head no. I don't think he was alone, I heard myself say. I was surprised to find myself choking back so much emotion. As long as I live I'll never forget that moment with Dr. Walp. Both of us had only intuition, our reasoning, and common sense by which to fly. Our gut feeling, and plain old common sense, told us that Luna, driving down the turnpike, did not stab himself thirty-six times, once through the back of the neck, before throwing himself into an icy December creek to drown. When you study the Luna case for any length of time you come to sense something else at play. You can almost feel the intelligence at work. Someone was in that car with him, and did this to him. And left no clues.

But who would be capable of doing such a thing? And how came a killer to be so good at leaving so few clues?

This is where hard evidence, and profiling, come in, not comic Hollywood, and certainly not karmic Bollywood.

Luna's Honda Accord (top) and Gricar with his Mini Cooper: 'At the very heart of the riddle, lies the remarkable debate: whether either man encountered anyone at all at the time of his disappearance.'

A large pool of Luna's blood was found in the right, rear footwell of Luna's Honda Accord, according to police records. Another smear of blood was found on the driver's door, and the driver's-side front fender. Luna, it seems likely, had been left for dead in the backseat footwell of his car. His assailant or assailants had fled. Luna, mortally wounded and in shock, appears to have revived himself long enough to get into the driver's seat and attempt to drive away. The car suddenly veered to the left, across a lawn, and ended up stuck on the raised lip of a creek bed. Luna, disoriented and terrified, got out of the car to hide. In so doing he smeared blood on the door and fender, before he splashed down in the stream, tucked under his car to hide, where he drowned.

What was the terror that Jonathan Luna saw, and that made him stumble into the frigid stream? The lack of physical clues makes his killer the Invisible Man. Hollywood, I'm sure, would show the scene from the invisible killer's perspective, with a horrified Luna backing away from the unseen monster. And in Hollywood's estimation, what would that monster be? The Blob, perhaps?

Well it's not The Blob, the Invisible Man, nor The Terminator. It's a real, flesh and blood man, or men, with a motive, and a carefully executed plan -- to terrorize the victim, and probably broader society. As with Ray Gricar, the plan behind Luna's vanishing smacks of being executed a little too carefully, with a calculated confusion. Consider Luna's strange, circuitous car ride across four states. Yet this was almost certainly not a random street crime, where the offender doesn't give a shit about his victim. The offender obviously cares a great deal about something, and acts in a way that also warns he knows how not to get caught. In Luna's case, it even appears the offender knows something about profiling, and actively set out to manipulate the crime profile to throw off investigators. Is it a disorganized crime scene, or one organized to look that way? Could this also be why Gricar's car was left at the river, if not by Gricar? To make investigators think suicide? Who would know how to do such things? And who would know enough about Jonathan Luna, or Ray Gricar, to pull that off?

Victimology

That's where Luna's victimology comes in. It's also where we see the great advantage of the public being able to see the hard facts of these cases, and not just spiritual communications.

'Joey wouldn't have liked that. These guys were out of control. That's not what Joey was about.'

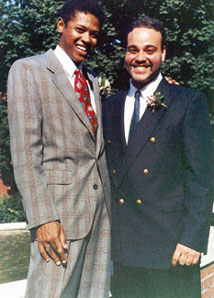

Joey Rivera (top) reflects on pictures of his old friend, 'Joey' Luna. Jonathan Luna (bottom left) on his wedding day, in August 1993, alongside best man Danny RiveraTo view more of Danny Rivera's photos of Jonathan Luna click here >>

One of Luna's closest friends, Danny Rivera, carefully read my book. Rivera spoke of Luna as Joey, Luna's nickname. In Part Two of the book, I painstakingly reconstruct Luna's last days in court, using the official federal court transcript. This section of the book eats up hundreds of pages. One of the enduring mysteries of the case is why a normally fastidious, sharp and competent trial lawyer like Luna made so many glaring and obvious blunders in the courtroom in the last hours and days of his life. Luna's seeming blunders led the judge to order an inquiry into the FBI.

At trial, Luna found himself prosecuting a case involving FBI negligence. A paid informant, Warren Grace, was allowed to continue dealing heroin while under FBI supervision, the court record shows. His FBI handler, Special Agent Steve Skinner, working with the "Safe Streets Task Force," didn't seem to care that Grace jumped home confinement and shot up his neighborhood. Neighbors' repeated calls of concern and outrage were ignored, Luna saw. When the Dawsons' house finally burned down, killing all seven in the family, Skinner's "Safe Streets Task Force" was no where in sight. Instead, Skinner's informant was found with heroin on the day the Dawsons' house burned. Over the months before their deaths, the Dawsons had called 911 thirty-six times for help. No help came from the "Safe Streets Task Force." Meanwhile, the record shows, Skinner's drug task force informant was himself dealing heroin.

"Joey couldn't have liked that," his friend says. "These guys were out of control. That's not what Joey was about. He really wanted to help people. He came from the Bronx, from a neighborhood like that himself." Victimology . By making obvious blunders in the case, his friend suggests, Luna forced the judge to hold an inquiry, to make Skinner and his drug task force accountable. Could this have led to his murder?

"You have to understand Joey," Rivera told me. "He was sly, and extremely smart. He didn't always do things straight on. He was smart enough to sometimes work below the surface." He cited a few amusing examples.

He goes on, "Joey couldn't have liked the stuff Skinner and the others were pulling. I know Joey. What could he do about it? Don't you see? He was trying to expose them."

"What?" I said, thunderstruck.

"That never occurred to you?" he said, surprised. "That stuff about leaving things back on his desk, and not knowing how to introduce evidence. Come on. I've been with Joey in court. He was sharp. That's not Joey."

Rivera tells me, "Joey was both street and book smart. And that made him dangerous to some people. Joey grew up in the projects. There's a scam running on every corner here. Joey just didn't walk into a street trap. He would have sensed that. And he was also a marathon runner. He could have just run away from them. Joey had to have been tricked, by someone he thought he could trust."

Someone he worked with, no doubt. And Luna worked in law enforcement.

Luna needed glasses to drive, yet mysteriously left them behind

Which brings us to another very odd part of Luna's mystery. Luna left his eye glasses, cell phone and laptop behind on his desk, in his courthouse office, when he vanished shortly before midnight, December 3, 2003.

Danny Rivera told me he wanted to show me something. He produced a remarkable photograph of Jonathan Luna driving an Accord, while wearing eyeglasses.

A nuanced mystery: 'Why would Joey leave his glasses back in his office? He needed them to drive.'

In this remarkable photo (top) Jonathan Luna is photographed from behind, circa 1993 or 94, wearing eyeglasses, which he needed to see to drive. Why then do the transcripts (bottom) of Luna's last case reveal he left his eyeglasses in his office before he vanished and was killed? Photo by Danny Rivera. Click either image to enlarge.

"Joey needed glasses to drive," Rivera says. "He always drove with his glasses. This picture was from 1993 or 94. Why would he go out driving at night without them? His eyes only got worse in ten years." Luna wouldn't have willingly driven without his glasses on a trip to the store, Rivera insists, let alone on a bizarre midnight trek across four states. "Why would Joey leave his glasses back in his office? He needed them to drive," Rivera asks. Rivera thumbed through his photos, and found a picture of Luna walking away from a car he'd been driving, again wearing glasses.

So why were Jonathan's glasses left behind on his desk before he vanished from the supposedly secure courthouse? We must, Special Agent O'Toole reminds us, consider the smallest behavioral detail or nuance.

Mystery thickens: alleged corruption in the drug task forces

Like Jonathan Luna, DA Ray Gricar left behind odd items. Gricar's cell phone and water bottle were locked in his car. Gricar's laptop, sunglasses, keys and wallet are missing. Gricar probably wasn't taking a hike without the water bottle, and with his laptop.

There are other strange similarities in the vanishings of both prosecutors. Both men were involved in heroin cases at the time of their disappearances. And both men were working with drug tasks forces whose effectiveness, to say the least, has been called into question.

The FBI's "Safe Streets Task Force," which plagued Luna's last days and hours, has already been mentioned. I've heard repeated complaints about similar drug task forces in Pennsylvania.

The members of one drug task force in central Pennsylvania, I've repeatedly heard complaints, for years has targeted out-of-state drug dealers for arrest. "They'll look for someone whose car they like," one Harrisburg private investigator tells me. "They'll bust him for drugs, and confiscate his car. The car is turned over to the local DA, who sends it over to a local car dealer and state highway department security provider, who then gives the drug task force officer back the car, along with a credit card for him to use."

This investigator described a horror show in central Pennsylvania that might better be expected in Mexico. "It's gotten so bad," he tells me, "if these guys see a car they like, they'll plant drugs on the guy to get his car."

The private investigator complains, as do others, that the systemic corruption is so bad that there is no mechanism for concerned citizens to report perceived wrongdoing, on the state or federal level. Pennsylvania state police are part of the task forces and surely know what's going on, he says. And, for some odd reason, the FBI can't be bothered to look into things.

Is that's what's going on in Maryland and Pennsylvania? If so, an honest prosecutor standing in the way of something like this could find himself in a world of trouble. And, if something, shall we say, goes horribly wrong, don't expect much more than a seance.

In the case of Ray Gricar of State College, Gricar himself said he worried about the rising incidence of heroin in his jurisdiction. I've heard complaints from police officers in the region about kids increasingly showing up with needle marks on their arms. Parents have told me they've had to move out of the State College area to get their kids away from it. The Centre County Drug Task Force, by Gricar's own reckoning, for some reason seemed unable to stem the tide.

And that tide keeps rising.

Ray Gricar's victimology

A portrait emerging of Gricar is one of a quiet, if fastidious, prosecutor who ran like clockwork and usually did things by the book. He was recently sued in federal court by a black man who alleged discrimination because Gricar did not offer an ARD to the plaintiff after the man drove, while DUI, the wrong way down a busy one-way street.

Gricar successfully defended himself in the suit by saying his office policy for years had always been to deny ARD to wrong-way drivers on busy one-way streets. He said he'd once offered an ARD to a black man who had gone the wrong way down a slow street, but had denied a white man the same leniency after he drove the wrong way down College Avenue, the main drag through State College. Maddingly, by the book.

Consider this: it only takes one bad drug task force officer to feel threatened by a DA who goes by the book.

Who you gonna call?

All this is happening at a very bad moment for the free press in the United States. In Pennsylvania, several high court judges have successfully brought lawsuits and won hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements against the Philadelphia Inquirer, and other newspapers and media outlets. One dead judge even successfully brought a multi-million dollar libel suit. Elsewhere around the country reporters are being threatened with jail, by a government that leaked the supposedly offending information to them in the first place. Those who bring these lawsuits and other court actions imagine the effect of all this is merely to bring our press to heel.

In actuality, the effect of all this is to bring down a curtain of darkness under which the safety of our prosecutors, law enforcement officers, judges, and other citizens, is threatened.

In the old days you could call a reporter. For a growing number of Americans, it doesn't seem to be worth the bother these days. Did you notice, they're no longer running stories on government and court misbehavior? I guess the problem's been cleaned up.

It's not the sound we have to worry about, former Inquirer editor Gene Roberts used to warn, but the silence. In the darkened cases of Jonathan Luna and Ray Gricar, that silence has grown ghostly, going on ghastly.

'By curbing press freedoms, we are creating conditions for a perfect storm of government isolation and indifference, growing drug corruption and violence, murder, and midnight disappearances.'

Instead of a thorough public airing of the record and the facts, we're offered psychics, and excuses. In both the Luna and Gricar cases, here's the story the mass media wants to tell: pictures of a tearful widow or loved one; cut to the chief, who says he's puzzled, but we're doing everything we can; cut to the psychic, who's channeling startling communications involving UFOs, a vegan sex fiend, and a red fire engine hook-and-ladder truck with the number 49 on it; bring back the crying loved one; cut to commercial. That's as deep into this, truth be told, as these corporate guys want to get.

Some of my least favorite people happen to write for newspapers. They can be jerks, and worse. In a pack situation I've seen normally decent fellows turn into dogs, seemingly losing all humanity, the journalistic equivalent of road rage. But at least they don't commit cold-blooded murder. We need the light of a strong and free press to keep corruption and tyranny at bay. Either we put up with the jerks, or expect legions of cold-blooded killers on the lose, as happens in many other countries.

President George Washington bitterly complained about the vicious partisan broadsheets of his day, which he fretted would sink the country into fratricide. Abraham Lincoln, while fighting the Civil War, saw himself regularly depicted in the press as a monkey, and worse. But neither man contemplated curbing our press freedoms. It's the yeast that raises our American loaf, and makes it healthy.

A strong, free press, which breaks the hard facts to the American people, and tells the public what is going on, and what is not going on, is what makes us American, and keeps us American.

By curbing press freedoms, and consolidating media ownership into the hands of the few, we are creating conditions for a perfect storm of government isolation and indifference, growing drug corruption and violence, murder, and midnight disappearances. That's what appears to be happening in Pennsylvania now, by my reading of the tea leaves floating by.

More than one hundred years ago, Samuel Clemens, aka Mark Twain, struggled to help publish the autobiography of Ulysses S. Grant. Sam noted he'd sunk every penny he had into Grant's last great project, his memoirs. He watched a destitute Ulysses Grant struggle, while dying of cancer, to write a book, and to be a man. Clemens suffered financial hardship by helping Grant. Clemens explained the hardship to his children by recalling there came a dark hour when a fire threatened to destroy America. While others stood in denial, or ran away, Twain said, Ulysses Grant had understood the emergency and began to stamp out the fire. Mark Twain believed it was his solemn obligation as an American to come to the aid of General Grant. The Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant was published to enormous commercial and critical acclaim, and restored the family fortunes of both Grant and Clemens.

Today another fire is burning. Joey Luna understood that better than most. He tried to stamp it out, and warn us. Now, we must stamp it out.

The disappearances of Jonathan Luna, and now Ray Gricar, are nothing less than a stern warning, and a test of our solemn resolve, as free Americans.

There appears meanwhile in Pennsylvania political and law enforcement circles growing recognition that it will be necessary to get to the bottom of both disappearances. At least one Pennsylvania DA, involved in a similar heroin case, has recently expressed grave security concerns to one of the state's most senior elected officials, I'm told. Solos have been known to swell into choruses, especially when the curtain's going down. Calls can already be heard for a thorough, public investigation.

There are no ghostbusters to call, my friends. We can, and should, summon the same spirit as those who made our country great. But let's not kid ourselves: The paperwork and the witnesses connected to the cases of these two men are the only concrete avenue we have to pursue. They must be pursued with vigor, if these investigations are to be taken seriously, and if they are to reveal the truth.

Who we gonna call? We in Pennsylvania must call on our congressional representatives for a full, complete, and public investigation into the circumstances, and hard facts, surrounding the cases and disappearances of Assistant United States Attorney Jonathan Luna, and District Attorney Ray Gricar.

Our country, America, is vanishing with them.