Bank robber robbed in Baltimore federal courthouseWere jurors misled about existence

of missing evidence?

Posted December 3, 2007 -- Almost forty thousand untraceable dollars, confiscated from the accomplice of a flamboyant Baltimore bank robber, would inexplicably vanish from the Baltimore federal courthouse sometime in September 2002.

The day the money was last seen, the cash was under direct care of an FBI agent working for the bureau's bank robbery squad, with at least one other FBI agent close at hand.

The money, it should also be noted, went missing under the noses of several assistant U.S. attorneys (including Assistant U.S. Attorney Jonathan Luna), a federal judge, U.S. marshals, sundry court personnel, and a defense attorney. Even so, at the time of his violent murder, Luna would be the one left holding the bag.

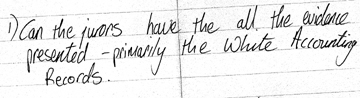

Circumstances surrounding the missing money are suitably theatrical, mysterious, even comic. A man named Nacoe Brown stood accused of violently robbing Baltimore banks while dressed in a series of increasingly outlandish disguises. He'd rob banks while wearing elegant suits, fedoras, and hospital scrubs. He also may have been commenting on our legal, medical, and entertainment professions. He stole more than $450,000.One day the law caught up with Nacoe Brown. The FBI's Baltimore Bank Robbery Squad arrested Brown's partner, Kevin Hilliard, and confiscated a safe containing $63,128. Soon thereafter Brown was arrested. The remainder of the $450,000 was never recovered. Hilliard later confessed that Brown told him he'd received a vision from God that they should rob banks to finance Brown's struggling Gospel dinner theater. Brown, curiously, also recorded a gospel CD titled, "In Love With You Lord," marketed by an independent gospel label in Delaware. Everyone in this story seems to have a CD. On his CD, bank robber Nacoe Brown croons songs like, "Jesus Can."

Jesus can, but Nacoe Brown couldn't. Brown was charged with robbing four banks. His case came to trial in September 2002, and was prosecuted by Luna and his co-counsel, Assistant U.S. Attorney Jacabed Rodriguez-Coss.

In addition to FBI Special Agent Steve Skinner's connections to the bank robbery squad, this case would have several other notable ties to the Smith-Poindexter investigation involving informant Warren Grace. Nacoe Brown's defense attorney was Kenneth W. Ravenell, the same lawyer who would later defend Deon Smith. And Jacabed Rodriguez-Coss would also, for a time, work as Luna's co-counsel in the prosecution of Smith and Poindexter.

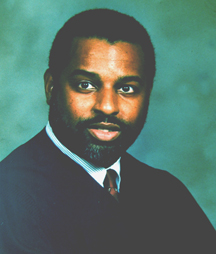

There were other, less apparent, yet more personal ties to Luna. The judge presiding over Nacoe Brown's bank robbery prosecution was federal district court judge Andre Davis. Judge Davis, and attorney Ravenell, were experienced black barristers who had taken young Luna under wing. Both Davis and Ravenell would later describe themselves as friends and even mentors to Luna. Judge Davis would later speak at Luna's funeral.After Luna's death, Ravenell would describe Luna as "a good friend." Ravenell would tell the Associated Press, "I was kind of his mentor in many ways. He'd call me often and discuss things outside of what we did on cases."

Shortly after the appearance of the third printing of this book, in late 2006, I received several letters from imprisoned bank robber Nacoe Brown. Brown had read my book, and now asked me to look into the missing money. Soon Brown was telephoning me from federal prison in Virginia and we were talking on the phone. Brown by this time was serving a 25-year sentence for his robberies.

It turned out that Nacoe Brown didn't just believe in old-time religion. Nacoe Brown has old-fashioned sensibilities, believing in honor among thieves and even lawyers. When such a man robs a bank, he naturally expects, when going to trial, the money won't be stolen by someone in the courthouse.

In a word, Nacoe Brown was upset about the missing money.

Nacoe Brown has had plenty of time to think about the prosecutor who put him behind bars.

At trial, which began on September 9, 2002, Jonathan Luna seemed to Brown like an experienced federal court lawyer. Luna "seemed like a professional," with "a college boy-type demeaner," Brown tells me. Luna was "very laid back, friendly."

Did Luna appear to be a competent trial lawyer? I asked.

"Definitely. Definitely. Definitely," Brown repeats.

I asked Nacoe Brown to recount events in the courtroom on the day he last saw the money, the third day of trial, September 16, 2002.

PDF Download:

3 pages in PDF format, including front and back of two jury notes and stipulation signed by attorneys in case that all evidence had been returned, "pending appeal"

Brown's accomplice, Kevin Hilliard, was on the witness stand telling the jury about the money they'd taken from the bank heists. "The reason why (the money) was brought into the courtroom was that it was confiscated out of my co-defendant's safe," Brown says. "And it had the bank wrap labels on it. And (Hilliard) was testifying that he robbed the banks, and so did I, and this was proof that he actually robbed the banks."

Several others were in the courtroom with the money beside Hilliard, Brown, and the jury. Judge Davis sat presiding at the bench. Also present was a court reporter, Sharon Cook, and court clerk Belinda Arrington; a bailiff; and "a couple" of U.S. marshals, Brown recalls. Brown sat with his attorney, Kenneth Ravenell, on the table to the right.

The prosecution table was to the left. Luna, Rodgriguez-Coss, and FBI Special Agent Anthony Compano sat at the prosecution table. Special Agent Compano was a relatively inexperienced FBI agent who had only been with the bureau a handful of years.

At the defense table, Ravenell sat to Brown's left, Brown says, between Brown and the prosecutors. A small group of Brown's family sat in the gallery behind.

When Brown was led into the courtroom at the start of the proceedings, he says, the $63,128 in recovered currency was already on an evidence cart in the courtroom at the prosecution table, under care of Agent Compano. At least one other FBI agent, Brett Kirby, court records indicate, also moved about in the courtroom as the evidence was on open display.

The money on the cart was in small denominations, Brown remembers. "Tens, 20s and stuff." The money, he says, " was wrapped in like big, sandwich-type bags." There were several bags of money. Each bag, Brown says, was "sealed, tight sealed. No one really could get into it. So that the jury could look at it in deliberations."

Brown described Luna as competently introducing the money into evidence as Hilliard testified. "They introduced it into evidence," Brown recalls. "Of course you know they just can't put it into evidence. They have to introduce the evidence. They have to introduce it through someone. And they did that through my co-defendant, by asking him to identify it. And he identified it, and they made their statements, and they went ahead and submitted it into evidence."

FBI Agent Compano, Brown says, "More than anyone was responsible for it (the money). He was there at the table with it. He was the one that really was handling the evidence, giving it to the prosecutors as they asked for it."

Brown continues, "I guess we know from watching tv is what he'll (Luna) do is (say), 'This is now people's Exhibit A,'" as he passes the money to the court clerk.

The trial transcripts indicate the bags of money were marked Government Exhibits 52A through 52G. (Even so, both Brown and Ravenell remember there were only three or four bags.) The bags containing the money had been "premarked" before trial by prosecution lawyers, Judge Davis later explained to the jury, "to help the court clerk." As Compano handed the sealed bags of money to Luna, Luna in turn handed them to the court clerk, where they were placed on a table in front of the judge, the jurors and the other onlookers.

The money "was given to the clerk," Brown repeats. "She handles all the evidence." The cash, Brown remembers, sat on the clerk's open table for several hours, through the testimony of two witnesses and over a lunch break.

At some point, in the courtroom, in the hallway, or perhaps even days later in the evidence vault, the money vanished. The missing bag of money therefore may even have been taken in the courtroom, over the lunch break.

Following Hilliard's testimony, trial transcripts describe Special Agent Brett Kirby taking the stand in the presence of the money to testify about how it, and other evidence, was found and sealed for court.

Under examination by Rodriguez-Coss, Agent Kirby first testifies, among other things, about a photo of the getaway vehicle used to rob the banks. "This is the vehicle that we believed to be the getaway vehicle that the defendant was sitting in, on the passenger's side in the front," Kirby tells the court.

Kirby continues, "We proceeded afterward to execute a search warrant at the residence of the individual who we believed to be the getaway driver and the driver of this vehicle, Mr. Hilliard."

"And what was your role once you arrived at that residence?" Rodriguez-Coss asks.

"Searching the residence with other agents that were present," Kirby says, "to attempt to recover any evidence that might be there, evidence of the previous bank robberies."

"Sir, during the course of that search, did you participate in the opening of a safe located inside that residence?"

"I did," Kirby says. "We found a safe in the bedroom closet. We utilized a tool to open the safe, which contained a considerable amount of money as well as some jewelry."

"I want to bring your attention to the items there in front of you which are marked 52A through 52G," Rodriguez-Coss says. "I want you to examine these items, sir, and can you tell me please, do you recognize these items?"

"I do," Kirby says. "I recognize these items as the money which was present in the safe that we opened at Mr. Hilliard's residence."

Also in the safe, and marked as Government Exhibit 101, were assorted items of jewelery. "There's a watch, a few rings, and a bracelet," Kirby testifies.

"And how is it that you recognize that item?" Rodriguez-Coss asks.

"I sealed it," Kirby explains. "And former (FBI) Supervisory Agent O'Hara, who was my supervisor at the time, witnessed it on that same date as the jewelry that came out of that safe."

"Now bringing your attention to what has been marked Government's Exhibit Number 53, can you tell me if you recognize this document?" Kirby is asked.

"Yes, ma'am, I do."

"Can you tell the members of the jury what that is?"

"This is an FD-302 Report of Investigation that I typed up subsequent to having counted this money," Kirby testifies. "I noted on the 302 that there was a portion of the money that on the straps around the bills was unmarked, had an unknown bank strapping. And then on each one of them, they had a stamp from a particular bank, all the way down, with a total at the end."

"What was that total, sir?"

"$63,128," Kirby replies.

Some of the money was traced to three banks. This cash, presumably, would be returned to those banks after trial. "From the Patapsco Bank, $3,600; from the Mercantile Bank, $6,478; and from the Key Bank, $14,950," Kirby testifies.

"And how much of the money was from an unknown source?"

"$38,100," Kirby says.

This untraceable sum of money, we have reason to believe, is the money that will soon go missing.

"I watched this evidence be introduced into the court through my co-defendant and identified by FBI Agent Kirby," Brown tells me. "I also watched this evidence stay in the courtroom for a long period of time and over the lunch recess."

After an afternoon court session, Brown says, he was led from the courtroom, never to see the money again. As he was led from the courtroom, the cash was still on the courtroom table, "with all the other evidence," Brown recalls.

Nacoe Brown by this time in his trial already had had several serious disagreements with his attorney, Kenneth Ravenell. Ravenell at the start of the case had requested a $30,000 fee, Brown says. But Brown says he'd only been able to give Ravenell $10,000.

So you didn't give him twenty thousand more dollars? I asked.

"He (Ravenell) was complaining about that all through the trial," Brown says. "All through the trial. It's all (in) the court records. And he was complaining to the judge about it. He complained to me about it."

On September 16, 2002, on the third day of the jury trial, the same day the money went missing, court records indicate that Ravenell asked the judge for permission to withdraw as Brown's counsel. The motion was denied. Ravenell's fee wasn't the only disagreement. At the start of the trial Brown, against Ravenell's advice, entered a guilty plea, only to withdraw it and change his plea to not guilty.

"In fact," Ravenell later would write the Maryland State Attorney Grievance Commission, responding to a complaint filed against him by Brown, "Mr. Brown approached the Court three times prior to trial indicating that he wanted to plead guilty. Each time he changed his mind stating to me that God would see that he prevail because God did not want him to be found guilty." Ravenell writes that he, "advised Mr. Brown against that strategy."

Rocky as things were between Brown and his attorney, Brown says he was unaware that Luna shared personal friendships with Judge Davis and Ravenell. Whenever Ravenell spoke of Luna, Brown says, Ravenell, "really didn't have anything bad to say about (Luna). I can't say he said anything bad about him. Up until the time of the missing evidence, or the murder, I didn't see any type of inconsistencies, you know?"

How did Luna act around Ravenell? I asked.

"The same," Brown says. "Like he knew him. You know, (they) interact(ed) with one another very well."

And how did Luna and Ravenell interact with Judge Davis?

This question sparked a memory in Brown. He recalled a moment during the trial when the three men stood together at the bench laughing at a comment made by Davis. This moment seemed to betray a closeness between the three men. "So it's like, for you to mention that, that comes back to my mind," Brown says.

The evidence used during trial was kept in a supposedly secure evidence lock-up vault in the courthouse. This is not like a locker in a gym where one keeps one's sneakers. It's a high-security vault, with sign-in and sign-out procedure sheets that detail evidence chains of custody.

At the close of each day's court proceedings, it was FBI Special Agent Anthony Compano's responsibility to oversee the money and other valuable exhibits as they were placed from the courtroom table back onto the evidence cart. By all accounts Agent Compano and Luna then wheeled the money on the cart through the courthouse hallways to the supposedly secure evidence vault.

"Luna and an FBI agent took the bags of money into the evidence vault," one courthouse worker told me, "and -- poof -- the money just vanished into thin air."

The money was officially discovered missing shortly after the last day of trial, on September 26, 2002, not long after both defense and prosecution lawyers signed stipulations that all evidence had been properly returned. Whether the money was unofficially known to be missing before that remains an open question.

On the morning of the eighth day of trial, September 25, 2002, the case went to the jury and Judge Davis gave his instructions to the jurors. Davis told the jurors, "The evidence in the case, which you may consider with respect to all charges and consistently with my instructions, consists of the sworn testimony of the witness, all exhibits received in evidence, and all the facts which have been stipulated.... A number of exhibits have been admitted into evidence in this case and will be available for your review." (Emphasis mine.)

Davis went on to tell the jurors, "After just a few minutes, after you go into the jury room, we're going to send in all of the evidence and copies of my instructions, as well as the verdict sheets."

In fact, Judge Davis wasn't telling the strict truth here.

The jurors began their deliberations at about 10:30 that morning.

Once the jurors left the courtroom, Judge Davis turned to Luna. Please see that the jurors are given all the exhibits, or evidence, the judge tells Luna.

Luna tells Davis, "We are going to meet with Ms. Arrington," the court clerk, to get the exhibits together.

Judge Davis asks Luna to please hurry, noting he'd had a "bad experience recently, where it took over an hour to get the exhibits together."

"We're not going to do that," Luna tells him.

"Frankly, I would prefer that you not wait until you've gone through all of them before you start sending them in," Davis goes on. "Get through as many as you can within the next couple of minutes, and then send those in, and then finish looking at whatever you need to look at, and send those in. They don't have to all go in at the same time."

"Yes, your honor," Luna tells him.

"Please take care of that expeditiously," Judge Davis says.

Trial transcripts reveal that there were other problems with evidence handling, and misplaced evidence, in this case. Ravenell now tells Judge Davis, "Your honor, I was just conferring with (court clerk) Ms. Arrington as to whether the exhibit was found that we couldn't find yesterday and she told me yes."

These assurances to the judge notwithstanding, it soon becomes apparent to the jurors that the prosecutors and the FBI have not given all of the evidence to them.

Certain items, including the money, are obviously missing from the jury room, and the jury sends several notes to Judge Davis asking, quite literally, in one note, to see all the evidence. This would turn out to be no small point. The exact wording of the notes from the jury -- what the jury wanted to see, and when -- become center to the controversy that follows.

One afternoon in October 2007, overcome by curiosity, I returned to the clerk's office in the Baltimore federal courthouse and pulled Nacoe Brown's bank robbery file. Inside the manila folder, attached to binders behind some court papers, I came upon a sealed, white envelope. The jury notes. The envelope had a look of unopened crispness to it. A few inches of Scotch tape sealed each side of the flap in the back. I gingerly opened the envelope. The tape, I saw, had never before been pulled from the back of the envelope.

Onto my lap poured an assortment of folded jury notes, written on lined spiral notepaper. Two of the notes spoke directly to the issue at hand.

"Can the jury have a list of all the evidence entered?" reads one note that was sent to Judge Davis at 11:45 AM on the first day of deliberations, September 25, 2002.

Twenty minutes later, at 12:05 PM, the judge was handed a far more specific note. It reads, in part, "Can the jurors have all the evidence presented -- primarily the White Accounting Records?"

This note quite clearly expresses the jury's desire to see, "all the evidence."

Receiving these two notes on September 25, Judge Davis calls the prosecution and defense lawyers back to the courtroom.

"Did we send in the exhibit lists with the evidence?" Judge Davis asks the prosecutors. No, he's told. There was no list of the evidence entered.

The problem, the judge is told, is that the evidence list was prepared before the start of trial and contains items that the prosecutors hadn't used. These items were marked on the evidence list for identification purposes before the trial. No longer an accurate list of evidence actually entered at trial, it wasn't sent in to the jury. A new list will have to be typed.

The real problem here, we now know, concerns the whereabouts of the evidence, not just the list.

Where's the evidence? the jurors are clearly asking. They could see that some items introduced at trial, including the cash, were not in front of them in deliberations, and they were asking about this.

"Belinda," Judge Davis tells the clerk, "we need Mr. Brown to be brought down. I'm going to bring the jury back into the courtroom and essentially answer all of these questions in one consolidated response.

"I'm going to tell them that we are preparing a sanitized copy of the exhibit list, that it's going to take a bit of time, but we will get it to them," Judge Davis goes on. "And I'm going to tell them that they cannot have any exhibits that were marked only for identification and that, in fact, they have all of the exhibits that have been admitted as evidence in the trial. Is that literally true, by the way?"

"Yes," Rodriguez-Coss tells him. The jury, she says at first, has everything except for a witness statement, which is now being re-typed.

"But all the money has gone in, and so forth?" Judge Davis asks.

"No, your honor," Rodriguez-Coss replies, contradicting herself.

"I didn't think you'd send in the money," Judge Davis says. "What money did you not send in?"

"We didn't send in any of the money," Rodriguez-Coss now tells him.

"None of the money," Judge Davis says. "Okay."

"Also, we didn't send in the pellet gun, and we didn't send in the pellets."

"Nor should you," Davis agrees.

Judge Davis calls the jury back into the courtroom. In the second note the jurors had asked to see accounting notes (referred to as the "White Accounting Records") that had been mentioned at trial by FBI Agent Compano. These accounting notes hadn't been introduced into evidence, and so could not be seen by the jury, the judge now tells the jurors.

"We have sent in to you, with a couple of exceptions, all of the evidence that was admitted in this case," Davis tells the jury. "We didn't send in the money, we didn't send in the exhibit which was the pellet gun, and we didn't send in the jewelry that was identified. I think, frankly, the reason we didn't send in those exhibits is pretty obvious. There are certain exhibits that we simply don't, under court procedures, allow out of the possession of the United States Attorney's Office and the FBI." Yuk, yuk.

If jurors want to see any of those exhibits, they can ask to look at them in the courtroom, Davis explains. "If you need to examine any exhibit that was not sent in to you, ...any evidence that was admitted but not sent in, simply send us a note that you want to examine whatever it is, and we will bring you back into the courtroom, as you are now, and ... we will allow you to examine that exhibit, including passing it among yourselves, if that's what you desire to do."

'Mollified, the jurors thereafter never again specifically ask to see the cash exhibits. Even so, they have been falsely assured the cash is there, should they want to see it. The next day, Thursday, September 26, 2002, the jury finds Nacoe Brown guilty on three counts of bank robbery.'

Mollified, the jurors thereafter never again specifically ask to see the cash exhibits. Even so, they have been falsely assured the cash is there, should they want to see it. The next day, Thursday, September 26, 2002, the jury finds Nacoe Brown guilty on three counts of bank robbery.

Following the guilty verdict, all that's left that day in court is housekeeping chores. The evidence lists used by the prosecution, the defense, and the court are tendered for entering on the docket. The lawyers sign stipulations that all evidence on the lists are accounted for.

Then Judge Davis orders that all exhibits in the case "be returned and retained."

Shortly after this the plastic bag containing the $38,100 in untraceable bills is discovered missing.

Agents in the troubled FBI Baltimore field office react to all this in a rather peculiar way. Bear this in mind: these agents were charged with protecting and guarding the evidence at this trial. They failed. The FBI agents have lost the evidence. Now FBI agents from the same field office are placed in charge of investigating their colleagues and themselves, and everyone else in the courtroom, to determine what happened to the missing cash, which the FBI agents themselves were responsible for and lost.

Right off the bat the compromised FBI agents do something rather interesting. They leak the story to the press.

Only one week after Brown's conviction, on October 3, 2002, the Baltimore Sun published an article written by Gail Gibson, titled, "Money stolen, found and missing again," subtitled, "Cash: Up to $38,000 used as evidence in a bank robbery trial has disappeared, officials say."

This article itself is curious, and would later become part of and referred to in the court disciplinary inquiry filed by Brown against his attorney, Kenneth Ravenell.

The Sun article begins:

As they wrapped up a two-week bank robbery trial in U.S. District Court in Baltimore, federal authorities discovered another possible crime -- some key evidence, more than $36,000 in cash, had disappeared.

From here out, the missing money would simply be referred to as "the missing $36,000," even though, it seems likely, the actual sum was $38,100. Gibson here also, rather clumsily, reveals her sources for the story to be FBI agents. Her article continues:

FBI officials confirmed yesterday that agents are investigating what happened to money used as evidence in the trial of Nacoe Ray Brown, who was convicted last week in a string of violent bank robberies in Baltimore County. Special Agent Barry A. Maddox, an FBI spokeman, declined to discuss the evidence investigation in detail or say how much money is missing. But law enforcement sources said that $36,000 to $38,000 was gone and the FBI agents had interviewed numerous courthouse employees this week.

The money was determined to be missing as attorneys packed up after a jury returned its verdict against Brown last Thursday, said U.S. District Judge Andre M. Davis, who presided over the trial and was astounded by the discovery.

Davis said investigators have indicated that the money apparently was not taken from his courtroom, but that it likely was lost somewhere between the courtroom and government storage used to hold sensitive evidence during trials.

"My understanding is it wasn't taken out of the courtroom, and that gives me a very narrow measure of relief," Davis said. "The bureau is undergoing a very thorough, professional investigation, and we can just await the outcome."

Officials with the U.S. attorney's office did not respond yesterday for comment.

Federal prosecutors and the FBI agents assigned to the case would have been directly responsible for the money. Such evidence, along with items such and guns and drugs, typically is kept locked in a secure area except for a brief period when it's introduced at trial.

This last sentence, stating the money was only displayed for "a brief period," is obviously wrong. It sat in open court through two long testimonies of two important witnesses -- Hilliard and Agent Kirby. And Nacoe Brown says it remained in the courtroom over the lunch break. It's also apparent that whoever is leaking this story isn't friendly to Luna. In fact, the article seems designed to put heat -- and headlines -- on Luna, and perhaps on his self-described "mentor," Ravenell. The Sun article goes on to report:

A stipulated agreement that all exhibits in the case had been returned was signed on the last day of the trial by each of the attorneys in the case -- Assistant U.S. Attorneys Jonathan P. Luna and Jacobed Rodriguez-Coss and defense attorney Kenneth W. Ravenell.

Ravenell said yesterday that at the trial, government lawyers asked Hilliard to identify the cash seized from his safe as coming from the bank robberies. Ravenell said the money was heat-sealed in two or three separate plastic bags and that each one was extremely bulky because the denominations were relatively small.

The missing bag of money contained as much as $38,000, apparently in $20 bills, according to law enforcement sources close to the investigation.

"Law enforcement sources close to the investigation." Read: FBI agents who are the Sun's sources for this story.

Next in the article, Ravenell is quoted as making a curious misstatement. For a sharp-eyed attorney like Ravenell, it's a very glaring mistake. He again repeats the false notion that the money was only in the courtroom for a "short period," during Hilliard's testimony. For some reason Ravenell forgets that Agent Kirby also testified in front of the cash exhibits:

Ravenell said the money was in the courtroom for only the short period when it was identified by Hilliard and introduced as evidence. After that, he said the evidence apparently was taken to a secure area by government agents or attorneys, who typically wheel case files and evidence boxes through the courthouse on rolling carts. "These were not like little stacks of ... hundred dollar bills," Ravenell said. "It's not something that, in my opinion, is just going to fall off the cart in the hallway and no one would notice."

Ravenell said he had not been interviewed by FBI agents and learned about the missing evidence during an unrelated appearance in Davis' courtroom this week. He said the evidence probe would not affect his client's case or sentencing, which is scheduled for December 13.

"The money was there during the trial," Ravenell said. "What they did with it afterwards, I have no idea."

This last statement was another curious observation by Ravenell. A close read of the records reveals it's not at all clear that the money was "there during the trial."

Nacoe Brown tells me he incredibly first learned of the missing money, not from his lawyer, but shortly after his trial was over, when his wife sent him a copy of the October 3, 2003 Sun newspaper article. Ravenell, he says, refused to raise the missing evidence as an issue with the court, at his sentencing, or in an appeal. Raising the issue of the missing evidence, Brown says Ravenell told him, would be "frivolous." All this mystifies Brown, now sitting in federal prison in Virginia.

"Ravenell is known on the street as being a defense lawyer who looks for any opportunity to get his client off," Brown tells me. Yet, Brown complains, "Ravenell didn't take advantage of this once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to point out the mishandling, stealing and withholding or (contamination) of exculpatory evidence. Even after I requested him to do so, he went out of his way not to let the record reflect what has taken place."

From Nacoe Brown's perspective, sitting at the defense table between Ravenell and Luna, the entire episode of the missing money smacked of chicanery, and legal slight-of-hand. When exactly had the money gone missing? Doesn't the FBI owe the public, and Brown, an explanation of the complete circumstances of its disappearance?

"Some men will rob you with a six-gun. And some with a fountain pen," Woody Guthrie observed.

What exactly would the FBI's Baltimore field office do about the missing money? The FBI launched what it described as an exhaustive investigation. Agents even twice interviewed Judge Davis. Davis says he provided trial transcripts to agents in the spring of 2003.

Early on, as we've seen, compromised FBI agents would leak information to the Baltimore Sun's Gail Gibson. And, early on, the FBI agents would curiously do so in a way that attempted to pass blame on to Tom DiBiagio's U.S. Attorney's office in general, and Jonathan Luna in particular.

The "missing $36,000" episode clearly and rightly grew into a major FBI embarrassment. The G-men got their panties in a bunch trying to get to the bottom of the mystery. There'd be lots of posturing, finger pointing, and butt covering, yet the bottom line was the money was gone, taken by someone, or several people, while under FBI guard.

The money didn't just vanish into thin air, whisked away by pixies, insiders know. And not just money was missing; trust had been misplaced.

It would grow into a major bone of contention between the Baltimore FBI field office and the U.S. attorney's office.